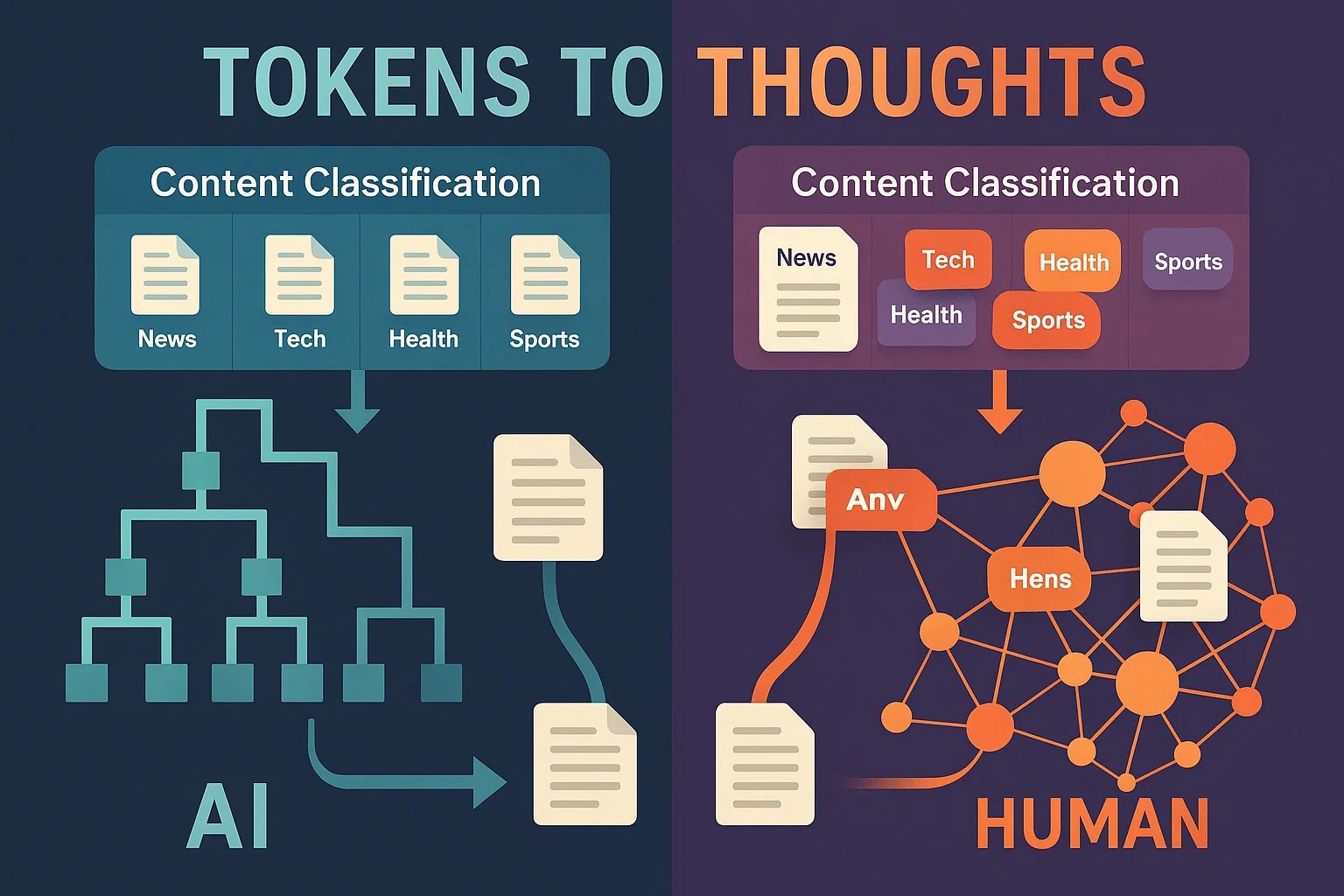

I recently read article “From Tokens to Thoughts: How LLMs and Humans Trade Compression for Meaning” by Yann LeCun and the team. Its target audience ii LLM professionals so I won’t claim that I understood the maths in it. But its content and conclusions resonated with me as a few years back I was facing a similar compression vs. meaning trade-off challenge while working on content categorization and taxonomies in Oracle Content Management Cloud (sadly, scheduled for end-of-life on December 31, 2025). In short, every content management system faces the same dilemma: tag a news article as “Technology” and lose the nuance that it’s really about AI ethics, regulatory challenges, and startup culture all at once. Whether you’re building tools for document categorization, image tagging, or knowledge graphs, you’re constantly trading semantic richness for organizational simplicity.

Your brain and modern LLMs solve this exact same problem when forming concepts, but research in this article reveals that they make fundamentally different trade-offs. The implications challenge core assumptions about AI scaling and suggest that the path to more capable systems might require embracing complexity rather than optimizing it away.

The Research Question

Do LLMs organize information like humans, or are they fundamentally different cognitive architectures? This question isn’t as obvious as it might seem. Large language models can perform many human-like tasks—writing code, answering questions, even engaging in creative reasoning. But their internal organization of knowledge might be completely different from how humans think.

Consider the difference between normalized and denormalized database approaches. Both can serve data effectively, but they make different trade-offs between storage efficiency, query performance, and maintenance complexity. Similarly, human cognition and AI systems might both handle information processing successfully while employing completely different organizational strategies under the hood.

Understanding these differences matters because current AI development largely assumes that scaling up existing approaches—more parameters, more data, more compute—will eventually lead to human-like intelligence. But what if that assumption is wrong? What if the architectural differences run deeper than we thought?

The Framework: Measuring Cognitive Architecture

Researchers essentially built a standardized test for “content classification algorithms”—comparing how humans versus LLMs categorize the same content. They used classic psychology studies (the Rosch datasets) as the base: thousands of items with human-validated category assignments and “typicality” scores that capture how representative each item is of its category.

Think of this as having a benchmark dataset where human experts have already labeled content with both categories AND confidence scores for edge cases. For instance, “robin” gets tagged as a highly typical bird, while “penguin” gets the same “bird” category but with much lower typicality scores.

Information-Theoretic Scoring

To measure performance, the researchers borrowed from compression algorithm evaluation: Rate-Distortion Theory and Information Bottleneck principles. They created a unified L-objective function that penalizes both over-complicated taxonomies AND loss of semantic meaning (don’t ask me how this function actually works 😊).

In content categorization terms, this scores how well your classifier balances having manageable category counts versus preserving nuanced distinctions between content items or images. A system that creates 1,000 micro-categories might preserve semantic richness but be unusable. A system with only 5 broad categories might be simple but lose crucial information.

Research Questions Interpreted in My Words

- Taxonomy Alignment: Do AI classifiers create the same category hierarchies humans would? This tests macro-level performance—whether AI and human classification systems would organize a content repository similarly.

- Confidence Calibration: Do AIs understand which items are “clearly Technology” versus “borderline Technology/Business”? This examines whether AI systems develop human-like intuitions about prototype examples and edge cases.

- Overall Architecture Efficiency: Which classification approach makes better trade-offs between simplicity and semantic preservation? This provides a quantitative way to compare the fundamental strategies different systems use.

The Experimental Design

The researchers tested over 40 models across the major LLM families—from BERT to GPT to Llama—on a corpus of 1,049 items spanning 34 categories. They analyzed both static embeddings (like traditional word vectors) and contextual representations (how models process words in context).

The aim was to systematically compare human versus AI content organization strategies using rigorous information theory, rather than relying on intuitive assessments or narrow tasks performance.

Key Finding 1: Macro-Level Classification Performance

LLMs build similar category hierarchies to humans, successfully distinguishing “Animals” from “Furniture” from “Vehicles” at the high level. All tested models performed significantly above random chance on broad categorization tasks, confirming that they do capture meaningful semantic structure.

But here’s where it gets interesting: smaller encoder models like BERT-large (340M parameters) frequently matched or exceeded the performance of models 100 times larger. This suggests that architectural choices and training objectives matter more than raw parameter count in the model for classification tasks.

The Scaling vs. Design Trade-off

The BERT family consistently showed strong taxonomy alignment despite being much smaller than modern decoder models. This challenges the “bigger the better” approach that seems to dominate current AI development. For content categorization specifically, purpose-built architectures might outperform general-purpose giants.

For ML engineers, this suggests that classification pipeline design choices have more impact than you might think. Before defaulting to the largest available model, consider whether encoder architectures might actually perform better for your specific categorization needs.

For product teams, this research indicates that smaller, purpose-built models might deliver better results for content organization tasks while requiring significantly less computational overhead.

Key Finding 2: Edge Case Classification Performance

While LLMs excel at broad categorization, they struggle with confidence calibration within categories. They have trouble distinguishing whether “penguin” or “robin” is a more representative bird—essentially failing at the fine-grained judgments that humans handle intuitively.

In classification system terms, they’re good at binary decisions (“Is this a bird?”) but poor at confidence scoring and prototype distance measurement. Your content classifier might correctly tag articles as “Technology” but fail to distinguish between core tech content versus borderline tech/business hybrid pieces.

Why This Happens

LLM training today optimizes for broad statistical patterns rather than human-like hierarchical understanding within categories. The models learn category boundaries effectively but miss the internal structure that humans use for nuanced judgments about content item typicality.

Even with massive training datasets, models fail to capture the subtle gradients that humans intuitively understand. This isn’t necessarily a data quantity problem—it appears to be a limitation in how current systems organize semantic information.

Real-World Impact for Content Classification

For content management systems, you should expect solid high-level categorization but plan for human review on edge cases and confidence scoring e.g., you can treat LLM categorization as recommendation that a human needs to review. Auto-tagging will handle obvious cases well but may mislabel or poorly rank borderline content where category boundaries blur. Using LLM for content categorization in terms of compliance, confidentiality level, or retention policies requires extra rigorous training

For search and discovery applications, this suggests that pure AI-driven content organization might miss the nuanced distinctions that make search results truly useful to human users.

System Design Implications

The research points toward hybrid approaches: use AI for initial broad categorization, then rely on human expertise for fine-grained distinctions and quality assessment. Design workflows where humans handle the nuanced classification decisions that require understanding of content item typicality.

Set up systems to flag low-confidence predictions for manual review, and consider confidence thresholds as a core feature rather than an afterthought. The goal should be robust human-AI collaboration rather than full automation.

Key Finding 3: The Classification Efficiency Paradox

Here’s the most counterintuitive finding in this article: LLMs are more “statistically optimal” at the compression-meaning trade-off by information-theoretic metrics. AI categorization systems achieve better mathematical efficiency scores—cleaner taxonomies with less information redundancy.

But this statistical optimal categorization might actually make them less useful for real-world content organization than human-designed taxonomies.

Why Human Classification “Inefficiency” Is Actually Smart

Humans deliberately create overlapping categories and preserve “wasteful” semantic distinctions. We maintain multiple classification dimensions simultaneously—topic plus audience plus intent plus sentiment. Human taxonomies handle novel content better because they preserve more contextual hooks for reasoning.

In Oracle Content Management Cloud we modeled “human approach” for capturing nuances by allowing content categorization against multiple taxonomies each representing different aspects of an image or document.

Consider Netflix’s recommendation categories. They’re not mathematically optimal, but “Quirky Independent Movies with Strong Female Leads” works better for users than statistically pure genre clustering. The “inefficiency” is actually functional design.

Technical Deep Dive: Measuring Classification Quality

Apparently, the L-objective function allows balancing category count (complexity) against information loss (distortion). AI systems consistently achieved lower L scores, indicating better mathematical efficiency. But as any PM or software engineer knows, mathematical optimization doesn’t always translate to user satisfaction or real-world utility.

Human-curated playlists often outperform algorithmic ones not despite their “inefficiency” but because of it. Corporate taxonomies that seem “redundant” to algorithms often reflect genuine business complexity that pure statistical approaches miss.

Why This Matters for System Architecture

Current LLM scaling assumptions suggest that more training data and model parameters will eventually bridge any performance gaps. But this research suggests a fundamental architectural difference that scale alone might not resolve.

The finding implies we should consider building systems that deliberately preserve “inefficient” semantic richness rather than optimizing it away. This might mean ensemble approaches that maintain multiple classification perspectives, or hybrid architectures that combine statistical efficiency with human-like contextual preservation.

For ML teams, this suggests being more cautious about optimizing away semantic redundancy during feature engineering. Include human-centered measures in your evaluation metrics beyond statistical efficiency. Consider preserving training examples that represent contextual complexity, not just clear category boundaries.

What This Means for AI Development

In MHO, this research challenges core assumptions about how classification systems should be designed and optimized. Statistical optimization alone won’t create systems that have human-like content understanding. We need classification approaches that prioritize adaptability and contextual richness over pure efficiency.

Practical Development Implications

I think that ML engineering teams, should consider multi-dimensional classification architectures rather than single-hierarchy approaches which would allow maintaining multiple classification perspectives simultaneously.

Using hybrid human-AI content agentic flow for content categorization vs. full automation seems to be a better strategy as the research suggests that human expertise remains essential for handling the contextual complexity that makes content systems truly useful. In terms of content management system design, it should be able to handle overlapping categories and contextual metadata and have a built-in flexibility to adapt taxonomies based on user context and task requirements rather than forcing everything into rigid hierarchies. The latter can be achieve by incorporating categories suggested by an AI agent.

Evolution of Content Categorization Pipeline

It seems that most teams currently optimize for accuracy and computational efficiency. This research suggests that human-like classification might require deliberately “inefficient” semantic preservation—a fundamental shift in how we think about system design.

In the longer-term content systems can benefit from adapting taxonomies based on user context and task requirements, rather than enforcing optimized but static organizational schemes.

Conclusion: Embracing Productive Classification Complexity

The most mathematically optimal content classification approach isn’t necessarily the most useful for real-world applications. Human “inefficient” taxonomies can preserve contextual richness that proves essential for adaptive reasoning and end-users satisfaction.

I think that the path to better AI-powered content systems might require embracing the perceived messiness of human information organization i.e., building systems that are useful content discovery and recommendation to humans. In a world increasingly dominated by AI-driven automation, this research reminds us that human-centered design principles remain not just relevant, but essential for creating truly intelligent systems.